Be sure to read Part I for Dan John's answers to questions 1-3.

- How do you choose between working with one or a pair of kettlebells?

I hinted about this subject when answering the previous question, but there are several issues to consider when moving to double kettlebells. The biggest issue is symmetry. Many of us are asymmetrical throughout most of our lifetimes. Yes, there are two lung lobes on one side and three on the other—and there’s only one liver and appendix. So yes, we are all naturally asymmetrical.

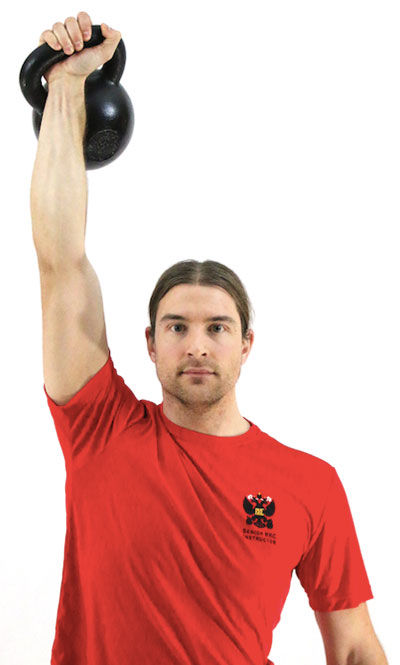

But, injuries, illness and age can make training an issue. This is why I am a champion of the one-arm press. Like the get-up, it is an assessment and a training tool. I have always seen five advantages to one arm pressing. First, the whole body must support the work done by one limb. This allows me to use more weight with one hand than I can handle with two. If I can press 110 pounds with one hand, I have two legs and one torso supporting it. Now, if I put 110 pounds in EACH hand, I still have two legs and one torso supporting it. While I know that I can press 110 with one hand, but double 110s (220 total) would be a great challenge.

My deltoids, triceps and the whole gang of muscles supporting this one arm lift will be really challenged. Yes, you can actually overload the arm—if you go heavy enough—with one-limb movements. True, the total amount is higher with two arms, but the local load is heavier with one. For hypertrophy, it almost seems like cheating. Second—and this should be no surprise—one arm lifting is asymmetrical.

The bottom line is simply that "asymmetry is harder." I strongly recommend that you use a partner or a mirror while practicing one arm lifting. The chin, sternum and zipper (my "CSZ Line") need to basically remain in a vertical line during the press. There will be some twisting and turning under great loads, but limit that as best you can.

Recently, I was asked: "What do I do when I start twisting?" I answered: "Stop." I thought that was brilliant.

Third, there is less equipment needed for one arm lifts. At my old gym, I had 113 kettlebells, but many of them were far too light for pressing practice. If forty athletes were all pressing with double kettlebells, they would need to share, which of course was fine.

But, by utilizing single kettlebells, the whole group could lift at the same time. There is something magical about watching that many people intensely focused on pressing weights up and down.

Fourth, using a light load and only one limb, there is a sense of what we call "active rest." There is an old story from the military: a bunch of privates are shoveling dirt. After a few hours, one of them asks "Sir, when do we rest." The officer answers: "Ah. If you throw the dirt farther, the dirt will be in the air longer. Then you can rest when the dirt is in the air."

Rest during one-arm lifts seems about the same as in that joke: you rest while the other limb is working. It’s funny, but the body seems more than able to support rep after rep while switching hands. Of course, the reps get challenging as you move along, but that brings us to the next point.

Finally, one arm pressing naturally leads us to "longer" sets. Now, if time under tension/load is the key to bodybuilding or hypertrophy, it makes sense that alternating hands and continuing to move would certainly increase time. Call Einstein for the specifics on increasing time, but those who have ever had a limb in a cast know that working on the healthy arm or leg seems to keep the atrophy of the injured side to a minimum. The body is one magnificent piece with only one blood system, so hypertrophy should come with these longer sets. In my experience, and with those willing to try it—it works.

The value of moving to doubles is obvious: you double the load!

- How does one choose a workout/sets per workout/reps per workout?

Let me repeat, I have spent my life trying to understand weightlifting. It seems to me that there are three important keys:

- Fundamental Human Movements

- Reps and Sets

- Load

Sadly, I think this is also the correct order that we should approach weightlifting. First, we need to establish the correct postures and patterns, then work around reasonable "numbers" of movements in a training session. Finally, we should discuss the load. Unfortunately—and I am guilty of this as well—the industry has switched the order and made a 500 pound deadlift the "answer" to improving one’s game or cutting some fat.

And, note well, that we’re talking about training sessions, not a workout—because these can also be a workout:

"Hey, go run to Peru!"

"Hey, go do 50,000 Burpees."

"Hey, go swim to Alaska."

But, please don’t think that will improve your skill set or your long term ability to do anything from sport to simply aging gracefully.

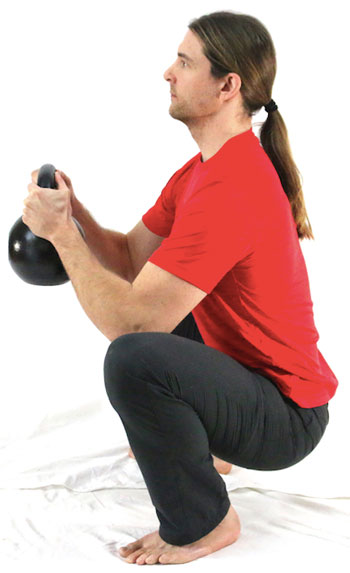

At the HKC, we learn what I consider to be the key patterns to human movement: the swing, the goblet squat and the get-up.

They are the same but different in their ability to remind the body of the most powerful movements it can perform. The get-up (not the "Turkish sit-up" as I often specify) is a one-stop course in the basics of every human movement from rolling and hinging to lunging and locking out.

So, the

HKC covers basic human movements in a way unlike any other system or school. As I often argue, if you add the push-up, you honestly might be "done."

The basics of proper training:

- Training sessions need to be repeatable.

- Training sessions should put you on the path of progress towards your goals.

- Training sessions should focus on quality.

The key to quality for most people is for them to simply control their repetitions.

When teaching the

get-up, or when using this wonderful lift as a tool to discover your body, keep the reps "around" ten. Now, you can think about this as a total of ten with five on the right and five on the left, or you can try ten right and ten left. But, please don’t make it a war over the numbers. Do the get-ups, feel better and move along.

I have noticed if I do get-ups as part of my warm up along with some get-up drills for "this or that" (the highly technical name we use for correctives) I am sweating and pushing into a "workout" around ten total reps. At times, you can certainly do more. But, week in and week out, think "around" ten reps for the get-up per session.

The

goblet squat seems to lock in at around 15-25 reps per workout.

One of the great insights—among many—I picked up at the

RKC is the idea of doing twenty swings with one kettlebell and ten swings with two kettlebells. After doing literally hundreds of swings a day, I noted that my technique held up fine within that ten and twenty range. It is the basic teaching of sports: don’t let quantity influence quality. In other words, ten good reps is far better than dozens of crappy reps. If you want more volume, just do more sets.

Of course there are times when you should do more than twenty swings—there are times when you want to do all kinds of things. But most of the time you just want to keep moving ahead. These "Punch the Clock" workouts are the key to staying in the game.

So, you may ask, is this enough?

Over time, yes!

It seems that 75-250 kettlebell swings a day is in the "wheelhouse" of the swing’s minimum effective dose. Yes, you can do more, but you want to be able to literally do it day in and day out—year in and year out.

Finally—and don’t take this as a joke—I mean it: if the kettlebell is too light, go heavier. And, if you went too heavy, try a lighter kettlebell. Combining swings and goblet squats with a big kettlebell is a killer workout. But, it is simple to scale it up and down by simply changing the

kettlebell. Yes, it’s that simple. If you look at movement first, then reps, for whatever reason, loading makes more sense, too.

The problem with programming is simple: the word "program" is sitting right there to start off the word "programming." And, programs are the problem.

It’s not an unusual week when someone emails me asking for a "program." It’s not unlike a patient calling a doctor to ask for medicine. This question is logical as a follow up:

"Um, for what?"

There are a million programs out there in books, magazines, and the internet. Most bodybuilding magazines will provide a dozen conflicting and complicated programs guaranteed to terrorize your triceps, pound your pectorals, and blitz your biceps.

There are programs for fat loss, muscle gain, and athletic peaking. I imagine they are all good and work perfectly as written. Sadly, few people ever follow a program for more than a few workouts.

Few of us ever actually FINISH programs. So, we end up with dozens of starts and misfires when it comes to following programs, and we miss the big picture.

Jim Wendler (inventor of the 5/3/1 program) recently wrote this about his mentor:

Towards the end of my senior year, I finally asked Darren why he never spoke to me during my first year in the weight room. And it was this lesson that I have taken with me in all areas of my life. His answer:

"Because you hadn't earned it. I've written hundreds of programs and helped so many kids and teachers with their training—and almost all of them quit after the first week. I had to see if you were going to stick with it. I had to see if you were serious. I'm not going to waste my time or my energy."

For most of us, programs are two to twelve weeks of following a structured workout that usually builds up to a peak week and a max. It is nice if there are easy days, maybe some deloading weeks, and some logical means of increasing load or volume—or both.

And most people quit their programs after the first week!

Programming is the

big picture. Armed with an understanding of programming, one can occasionally shift into structured two to twelve week training blocks to address issues and fix problems.

There are three keys to understanding programming. They come from the HKC manual, but are expanded in both the RKC and

RKC II certification curriculum. The keys are:

- Continuity

- Waving the Loads

- Specialized Variety

Understanding these three terms and applying them appropriately to any training model, piece of equipment or situation will allow you to progress towards any body composition or athletic performance goal.

Continuity

The secret to success in life is usually pretty simple. Woody Allen once noted: "90 percent of success is simply showing up." The same is true in fitness and performance: pack in enough workouts and training sessions over time and good things will happen.

Good things happen when we focus on continuity in our training.

Pat Flynn summarized training like this:

- Train consistently for progress.

- Add variety for plateaus.

- Randomness for fun.

Continuity can be summed up as "train consistently for progress." That is nothing new. Most of us know the story of Milo:

Milo was a wrestler and multi-time Olympic champion in the original Games. His father-in-law was Pythagoras, who made life easier with his idea, "The sum of the areas of the two squares on the legs (a and b) equals the area of the square on the hypotenuse (c)." We are told that Milo also consumed twenty pounds of meat, twenty pounds of bread and eighteen pints of wine daily. But, that is not why we remember Milo. It was his idea to pick up a bull.

The story goes that each day he would walk out to the pasture and pick up a certain calf. He repeated this every day until the bull was fully grown. Milo is the father of progressive resistance exercise and it’s his fault many people think that success in strength training happens in a straight line. I have joked many times with new lifters that if you bench 100 pounds today and add only ten pounds a week, about a year from now you will bench over 600 pounds. Well, it works on paper.

At some level, we all know Milo was right. During and after World War II, Dr. Thomas DeLorme and Dr. Arthur Watkins were working with polio patients and the injured soldiers. In 1945, DeLorme wrote a paper, "Restoration of muscle power by heavy-resistance exercises," published in the

Journal of Bone and Joint Surgery.

In 300 cases, he found "splendid response in muscle hypertrophy and power, together with symptomatic relief," by following this method of 7-10 sets of 10 reps per set for a total of 70-100 repetitions each workout. The weight would start light for the first set and get progressively heavier until a 10RM load was achieved. Over time, the workouts changed in terms of volume. By 1948 and 1951, the authors noted:

"Further experience has shown this figure to be too high and that in most cases a total of 20 to 30 repetitions is far more satisfactory. Fewer repetitions permit exercise with heavier muscle loads, thereby yielding greater and more rapid muscle hypertrophy."

A series of articles and books followed recommending 3 sets of 10 reps using a progressively heavier weight in the following manner:

Set #1 - 50% of 10 repetition maximum

Set #2 - 75% of 10 repetition maximum

Set #3 - 100% of 10 repetition maximum

In this scheme, only the last set is performed to the limit. The first two sets can be considered warm-ups. In their 1951 book,

Progressive Resistance Exercise, DeLorme & Watkins state: "By advocating three sets of exercise of 10 repetitions per set, the likelihood that other combinations might be just as effective is not overlooked… Incredible as it may seem, many athletes have developed great power and yet have never employed more than five repetitions in a single exercise."

I love that last line.

At around the same time, Vladimir Janda—the physician and physical therapist—began publishing his great insights about tonic and phasic muscles, and various "crossed syndromes." It is also important to note is that he was also a victim of that terrible disease of the last century, polio. Janda’s understanding was that stretching (loosening) one muscle and strengthening its opposite would promote better structural integrity than just attacking one side of the equation.

Janda also taught us that certain muscles ("tonics") tighten when we get ill, injured or with age. The pectorals, biceps, hip flexors and hamstrings are key for most people. Other muscles ("phasics") weaken when we get ill, injured or with age: these include the glutes, deltoids, triceps and abs.

The Hardstyle Kettlebell Three work miracles to counteract both the stretching of tonics and weakening of phasics.

Continuity of training embraces the idea that we need progression, specifically reasonable progression. Sold training and programming considers building the load, reps, and the sets up over time.

But, we also have to be realistic. I have had to sit down with many proud fathers and explain that their belief in their child’s linear progression does NOT hold up under the lens of common sense.

If Billy benched 100 pounds as a 14 year old. Dad projects Billy’s improvement to be about ten pounds a month. So, next year, Billy will bench 220, which seems doable. The next year after that, when Billy is 16, Dad expects a 340 bench press and I begin to wrinkle my nose. At 17, Bill (he is now grown up), should be benching 460. You can see where this is heading.

To improve in every field and quality of life, we must remind ourselves of my college coach’s key to success, "Little and often over the long haul." Ralph Maughan knew athletics and life. "Little and often over the long haul" should be one’s mantra for most of life’s work.

Continuity is:

- Showing up

- Training consistently for progress

- Progressively adding volume or load

- Being reasonable about expectations

Once you embrace continuity, we can shape our workouts with "waving the load."

Waving the Load

To understand Waving the Load, you need to consider three terms:

Volume is a math problem. If you’re using just one kettlebell, this is a pretty simple operation:

Add up all your reps in your workout(s) and compare them to other workouts.

Volume is the tough one for me. Pressing ten total reps with a 48kg kettlebell is the same "volume" as twenty reps with a

24kg kettlebell. Determining which workout is harder (

48kg for ten versus 24kg for twenty) has been the subject of discussion in lifting circles for generations. There is a method for figuring out an appropriate "volume to load" ratio for Olympic lifters and I applaud it. But, there are issues when adapting it to other lifting modalities.

Carl Miller introduced an interesting concept to Olympic lifters in the 1970s. It was called "K Value" and it is based on a formula. Now, Olympic lifting is judged by tallying the best of two lifts, the snatch and the clean and jerk. So, the contest total will be the sum in the discussion.

K Value (I thought of saying "simply," then I caught myself) starts with the following information:

- The total load of training.

- The total number of repetitions.

- The "total" made at the competition (the sum of the best snatch and clean and jerk)

Item A is determined by the total number of repetitions done with each weight (in kilograms) lifted in the major exercises. So, the athlete needs to multiply each weight lifted by the number of reps completed.

Then, we take the total load (A) and divide it by the number of reps (B). So, now that we have load divided by reps, we then multiply THAT number by 100. Finally we divide that number by the "total" made at the competition (C).

The Bulgarian Olympic lifters at the time had average K-Values of around 40 and most Americans were in the lower 30s. It demonstrated that the Bulgarians were really pushing load with their volume—a tough thing to do!

Considering that a lifter might have 700-1000 lifts in a training cycle, I think you get a sense of the issue with K-Value, the MATH!! My coach, Dick Notmeyer, had me do this math equation one time and I learned to stop asking so many questions!

Of the three terms (Volume, Intensity and Density), it’s the hardest to convince people that "more volume is not better". Yes, I am a champion of things like "The 10,000 Swing Challenge," but crappy swing technique will do far more damage than good.

My advice for volume:

- Always consider load when increasing volume. Doing more reps with a lighter load has great value, the 100-rep RKC snatch test is a good example. Light loads with volume have a "tonic" effect, in the old use of the word…it makes you feel better. But, enough is enough.

- You should only rarely increase volume more than 50% of your current level. One issue with the 10,000 Swing Challenge is that many people go from their usual 75 swings to 500 swings in their first workout. Yes, it is doable, but the hands and grip take a beating that might have been saved by easing into the reps.

- If you are preparing for performance, cut volume and focus on other qualities.

- Generally, when volume goes up, intensity (next discussion) tends to go down. It is true that the answer to the classic question, "Which is better: high weights or high reps?’ is "Both!" But, those of us who are mere mortals can only handle so much.

To truly understand volume, we need to discuss intensity.

Intensity

I’m not sure if there is a more confusing word in fitness and training than intensity. Yes, it is the amount of weight used in training. Yes, it is how close you are to failure or missing the lifts.

The devil is in the details.

When Arthur Jones sold his Nautilus machines through massive advertisements in

Scholastic Coach magazine, he redefined intensity. It became the rep an athlete failed with perfect form (on a machine). Others define intensity by how much vomit ends up in a bucket. And some define intensity by the percentage of maximum lift.

The last definition is good, but fraught with issues. I have a different set of terms for the word "max."

From "Sorta Max" to "Max Max Max"

First, let's look at three highly scientific terms that I use on a daily basis:

- Sorta Max

- Max Max

- Max Max Max

The Sorta Max

Most people have a "Sorta Max." A Sorta Max is a concept that I came up with a while ago when people were telling me about their "max's" in various lifts. The Sorta Max is that heavy lift you do in the gym—and then call it a day. And hats off to you, you deserve it.. That's great, and there’s nothing wrong with it. It's the heavy "today" max, if you will.

For many of us, we occasionally have a good day and nail a big lift, or in some cases, we just have a great performance. And these numbers are what most people call their "max" numbers. I define this as the Sorta Max

The Max Max

Max Max is the next step. That's that top end lift that maybe you spent the better part of a few months building up to with some kind of organized program. For the record, that's exactly what my best bench press reflects.

On at least three separate occasions, John Price and I decided that both of us needed to bench press 405—four big plates per side—and focused on the bench for two workouts a week. Those workouts were very simple, and we just tried to push our reps up. It always worked.

If I had spent more than just a month working on the bench, I'm sure I could have done more. But, for me, 405 is/was my Max Max. A few weeks of training focused on one lift and I made a good number, 405.

In my opinion, the Max Max is the most underappreciated measure in sports and training. It's simply what you can do with some effort. If all your Max Max numbers are at a good level for your goals and interests, I can practically promise you that you have achieved a solid level of strength in your chosen field. It might not be the best, but you're good.

The Max Max Max

Now, it should be obvious where Max Max Max is heading. This is a number that takes a lot of commitment and a lot of time to achieve. You'll probably need to do it in competition. All my top lifts are done in competition. Why? Well, there's usually a story...

Why a 628 deadlift? Because after I pulled 606, a bunch of other guys missed, and then one or two went up and made a big show of missing something a bit heavier. Since I wanted to make sure there was no question, I took the next poundage (628) up and made it.

So, Max Max Max might be a lifetime achievement you’ve planned for decades or, like me, you simply stumbled around long enough to do something "max-worthy." And that's also the issue with Max Max Max. When novices plot out a "Max," we need to ask this follow up question: "what do you mean by max?" I have been to many RKC certifications and talked with someone who had a "max" kettlebell in a lift. A day of coaching, demonstrating and practice often leads to a new "max."

While any and all training that was based on the old "max" numbers certainly had value, they were probably underloaded—and there is nothing wrong with that!

There is great value in playing with variations of load and intensity.

Low volume/low intensity: we practice skills and actively recover in these often underappreciated training sessions.

Medium volume/medium intensity: these sessions should probably make up 3 out of 5 your workouts. You get the work in and finish feeling better than when you started. These sessions won’t be posted on social media, but these are the ones which lead to growth and change.

High volume/high intensity: these are the sessions we brag about later. Generally, we take our time building up these sessions and need easy days afterwards. An example would be the five ladder and five rung day of the Rite of Passage. For this workout, I did 75 clean and press with my left hand, another 75 with my right hand and 75 pull ups. After that, I did a ten minute snatch test! That is a lot of volume. In addition, I only had my

28kg kettlebell at the time, so the intensity sneaked up very high.

High volume/low intensity: used appropriately, these workouts can be part of the building process towards a peak or improved performance.

Low volume/high intensity: these sessions are designed to push through a new max or limit lift. Like high volume/low intensity, these workouts are crucial for building up to a peak.

Good programming uses all five types of sessions. Generally, week in and week out the focus on the medium volume/medium intensity method for most of the workouts. Mix in perhaps a low volume/high intensity day with a low volume/low intensity recovery day. One can train for a long time on a program like this.

Plan the "low/low" days after any kind of "high/high" day. I generally suggest this group of five workouts:

- Three medium/medium days

- One "high" day (volume or intensity)

- One low/low recovery, tonic and practice session.

If you take on weeks of "high" on either side of volume or intensity, be sure to plan some sessions of the opposite with low/low mixed in afterwards.

For example, after the twenty days of 500 swings (The 10,000 Swing Challenge), we shift over to three days a week of mobility/tonic workouts focusing on 75-150 swings total along with stretching, rolling, and mobility work. There might be one "heavier" session during the week focusing on heavier grinds.

Density

Density is getting the work done in less time. With volume, the tool is the calculator, or in my case, an abacus. With load, the tool is simply the heaviest kettlebell you move. With density, the calculation tool is the clock.

More work. Less time.

There are two ways to attack density. First, and probably the most obvious, is completing a workout while noting the start and end times. Then, the next time you do the same workout, you finish it faster. That’s it.

For many, the problem will be obvious: racing through a workout often leads to poor technique. But, you MUST have quality control. It’s hard to put the kettlebell down "like a professional" while you are still panting and heaving. It’s a matter of discipline. If you can’t insure proper technique, proper performance and proper safety, stop and slow down.

It’s a race against yourself that you want to repeat some time soon, so don’t lose your future trying to win today.

Another method is work to rest ratio. Let’s look at the most common ratios:

1:1

This ratio can be difficult. Generally, this is 30 seconds on then 30 seconds rest (or active recovery). If we are doing kettlebell swings, you will swing for 30 seconds and then do "Fast & Loose" drills for 30 seconds.

For many trainees, using shorter time intervals is an issue. 15 seconds on and 15 seconds off often requires a level of skill and precision that many people simply don’t have…yet.

Practiced with a partner, the 1:1 ratio method is known as "I go/you go."

1:2

This is the work to rest ratio we use in "cohorts." Cohorts are three person groups training together. The rest period increases by the addition of another person. "I go/you go/you go." For exercises that need more recovery—double kettlebell front squats for example—the 1:2 ratio gives the body time to recover before performing another set.

1:3

This ratio is how I learned to lift. We worked in groups of four and everyone took their turn. The 1:3 ratio is very good for grinds, Olympic lifts and powerlifts in group and team settings.

Tabata

This pattern is twenty seconds of movement followed by ten seconds of rest repeated for a total of four minutes. I think Tabata works with squats and honestly, nothing else. It is a workout that leaves people in a pool of sweat while their dog tries to call 9-1-1…without thumbs! Tabata is a popular workout that has been so bastardized that its original vision has been lost. Use it with common sense.

Density Training

Density training probably makes for the best kettlebell workouts. Doing the same workload in less time works well with kettlebell ballistics and workout complexes like double kettlebell clean and push jerks. I would suggest using heavier kettlebells, or changing the workout after completing five workouts where the same workload is completed in less and less time. But, as good as density can be, enough is enough.

Specialized Variety

Specialized variety can be summed up in two ways:

- "Same, but different"

- "Fun"

Pat Flynn’s other two principles apply here: "Add variety for plateaus" and "Randomness for fun."

Most people who have trained for a while know the basics. If we’re training with barbells, we might switch out front squats for back squats, or the incline bench press for bench press. When Dick Notmeyer had me do back squats after four years (!!!) of just front squats, I felt like a new man. It was basically the same thing, but it was actually fun.

If you are bored with two hand kettlebell swings, shift to one arm—or do double kettlebell swings, or dead stop swings, or…

The

HKC, RKC and RKC II manuals have multiple pages devoted to examples of different moves and variations for every basic movement.

But…

Specialized variety is not just for fun or an attempt to deal with boredom. Biology teaches us that we adapt to stress and stimulus. We learn to accommodate (the law of accommodation) and improve at a task with less and less effort.

For body composition training, which is usually fat loss, we need to use the concept of "inefficient exercise." Simply, if you are really good at something, you probably won’t stress your fat reserves doing that movement.

If you were a former collegiate swimmer and put on fifty pounds of fat, swimming—especially now that you are more buoyant—might not be a good fat loss option for you. You are too talented (and floaty) to be sufficiently challenged by swimming laps.

Here’s another example, I have a neighbor who has a tricked out racing bike, aerodynamic helmet, and, yes, a white spandex racing suit. White... as in "almost see through." He also has a magnificent beer belly. His problem is simple. His bike rolls effortlessly around our streets and he doesn’t need to work very hard to get in all his miles.

My bike is a cruiser. It weighs about seventy pounds and has a built-in bottle opener. It’s a struggle to peddle my bike up a small incline. Riding one hundred miles on this big tire, beer-holding bike would take a lot of effort!

If you can’t swim well, struggling back and forth in a pool is a great workout. If you float and glide, it might not be much of a day.

Inefficient exercise drives fat loss.

When you get too good at certain moves, even though you might drive the reps up, you still might not increase the energy usage. One of the things we notice in "The 10,000 Swing Challenge" is that towards the end, we have figured ways to save energy. We have learned to "cheat" the swing. We become "efficient."

So, we need to change the exercise with specialized variety. We will still do the basic movement, but will choose a different variation.

Simplified Programming

With an understanding of volume, intensity and specialized variety, we can now move into the basics of programming. I always start with the fundamental human movements as my guide to appropriate programming:

- Push

- Pull

- Hinge

- Squat

- Loaded Carries

- Everything Else

"Everything else" can be tumbling, lunges, monkey bars, correctives, and everything else. These movements—especially anything done on the floor—often have great value beyond fitness and performance and venture into the realm of survival. If you need to crawl to safety, save your joints in a fall, or climb out of harm’s way, the "everything else" skills will trump a big bicep curl.

Loaded carries and hinges build athletes. The loaded carry family trains the body to work as one piece and provide the stability Stu McGill calls "Stone". When you hinge into someone and turn to stone, you will hit that person hard. These two movements are the key to athletic performance.

The push, pull, and squat are all hypertrophy and power/strength movements. I have one rule: the volume of push, pull, and squat numbers must be exactly the same each week. When you send me a "program" I look for two things:

- Gaps: which fundamental human movements are you NOT doing?

- The balance of the push, pull, and squat numbers.

I find these volume numbers often vary over a week for American lifters:

Push: 237 reps

Pull: 135 reps

Squat: 15 reps

This is why I love Delorme’s "basically" 15 to 30 reps in an exercise.

The classic workouts reflect this:

3 sets of 8

5 sets of 5 (Reg Park workout)

5 sets of 3

3 sets of 10 (as seen above)

Doing the same reps and sets scheme for the push, pull, and squat insures that there will generally be a balance in the body. Many American males need to add more pulls to their workouts to balance the years of favoring pressing and pushing.

Some "Rules" of Simplified Programming:

- Do all of the fundamental human movements.

- The push, pull, and squat rep numbers must have the same totals.

- Use the hinge and loaded carries families to increase athletic qualities and work capacity.

- Include enough of "everything else" to keep the client functioning and safe.

- Is it beneficial to run for extra cardio on top of kettlebell workouts?

This is a common question... along with these other questions:

Can I add bench presses to this?

Can I add ab work at the end?

Can I do more?

It’s a tough answer. I usually suggest that people try a program for a few weeks

THEN add more to it. Or my other, snarky answer is, "Do the program for six weeks

THEN make it perfect with your insights."

Many people have successfully

combined running and kettlebell work. I would suggest long walks interspersed with sprinting rather than bone-jarring jogging, but your miles may be different than my miles. I do have some ideas that might help you combine kettlebell training with running.

Like many, I have moved a few times in my life. Dragging training equipment over a few state lines is very expensive—and a royal pain. Through the years, I have purchased and re-purchased several Olympic bars, various smaller weights and many other pieces of training equipment. My gym today is still a collection of odds and ends, but my favorite equipment and training still has one key:

Free.

I love pure exercise. After every lifting workout, weather permitting, I go outside and play catch with a football, Frisbee or medicine ball. Jogging back and forth while yelling "I’m open, I’m open" is still just pure fun. Training outside gives you sunshine, some extra "cardio" or whatever, and reminds you of the athlete you still should be today.

I make my living selling training solutions to people, and I have a little combination that you can use today. It can be done outside or in many gym settings. You can chose to keep it simple, or feel free to add a few of my extra suggestions.

The combination uses two movements you already know: push-ups and sprinting. With the push-up, I ask that you keep your heels together, squeeze your knees together (I often joke that this is "how Utah teaches birth control"), and try to crush walnuts in your armpits. I want a lot of tension here.

Feel free to jog, run, sprint, or just stride for the sprinting portion. No matter what you choose, combine your running with push-ups. There are probably a million variations, but here are several simple ideas.

Basic Idea:

Do a set of ten push-ups. Pop up off the ground and accelerate, then ease off for about a total run of 100 yards. Pop back down on the ground and do ten more push-ups. Try this combination for three times total at first:

- 10 Push-ups

- Run

- 10 Push-ups

- Run

- 10 Push-ups

- Run

- 10 Push-ups

That’s 40 push-ups and about 300 yards of running. Did you notice something? You get tired from getting up and down from the ground! What used to exhaust me in football wasn’t just the hand fighting, the sprinting, and the collisions, but getting up and down over and over and over.

Feel free to increase the total number of combos, add more push-up reps, or increase the running distance. I would also suggest that you consider cutting back the reps to as few as one while decreasing the distance—but increasing the speed.

If you want to try something a bit more "leggy," bring out a kettlebell for goblet squats, then drop the kettlebell and sprint away. I use this variation for anyone in a collision sport or collision occupation to teach that odd "gear change" necessary for dealing with multiple priorities. You can also mix goblet squats, push-ups, and sprints into a delightful "one stop shop" for conditioning.

Training never has to be complex, in fact it should never be complex. Try to stop worrying about every detail and every percentage, get out there and have some fun again.

Well, there you go. Good questions lead to good answers.