The Kettlebell Posture

Dr. Jake Caldwell, DPT, CSCS, RKC

September 22, 2008 01:18 PM

We all know how important good posture is, but how many of us feel that we truly understand what that is? As a physical therapist, I see many people from all ages, with various injuries, and in various stages of dysfunction. I can say that very few people, even high-level athletes with years of fitness training, have any idea what optimum posture is. Common conceptions of good posture are far removed from the optimum posture that we should all strive to achieve. In this article, I hope to convey at least a basic understanding of what optimum posture feels like and what to do to achieve it.

Tonic and PhasicFirst, we must understand that muscles fall into two basic categories: tonic and phasic. Tonic muscles are designed for endurance; they can contract all day with minimal fatigue. These tonic muscles are our postural muscles. They are designed to maintain our position against gravity throughout the day. It is often easiest to think of our tonic muscles as our "core muscles" (although I can't stand this fitness buzz-word and strive to use it as little as possible, it does help to get the point across). Phasic muscles, on the other hand, are fast-acting. They are for making large and fast movements (like lifting a kettlebell). Both types of muscles are vitally important to overall health and fitness, and neither should be emphasized at the expense of the other. Most importantly, we should not rely on our tonic muscles to perform large and powerful movements (the phasic muscles should do those activities), and we should not rely on our phasic muscles for endurance activities such as maintaining our posture all day (the tonic muscles should do that). It is just this problem, relying on phasic muscles to perform the tonic activity of maintaining our posture, which leads to many injuries and is one of the primary problems with poor posture.

Figure 1. Slouching: the Lazy Approach to LifeSlouchingLet's discuss what optimum posture isn't. Most people slouch (Figure 1). We all know this is poor posture. It's the posture of laziness: the body is resting on its ligaments with very little postural muscle activity involved. Even though it sounds easy to rest on the ligaments, in actuality many muscles are involved in maintaining a slouched posture. The muscles involved, however, are not our tonic muscles, but our phasic muscles. In a slouched posture, the phasic muscles of the back of the neck, upper back, and front of the hips, to name a few, are being forced to contract all day to keep the sloucher upright. These muscles become irritated quickly and are usually areas of pain, discomfort, dysfunction, and injury. There are many other problems with slouching too: adverse joint positioning (can lead to early arthritis and joint injuries), poor ability to initiate movement (because the body is not aligned in a position of readiness), and poor stability (because the body is not using its stabilizing muscles: the tonic muscles).

Figure 2. Military-style Posture: Tight in all the wrong places.Military PostureMany people try to solve their slouching problem by telling themselves to "Stand Up Straight!" These people take on a military-style posture (head and shoulders pushed back, extended spine, etc) (Figure 2). But in reality, military-style posture causes just as many problems as slouching. The phasic muscles are purposely being used to maintain the military-style posture and these muscles will fatigue quickly. This is why when most slouchers try to correct their posture they can only maintain the "correct" posture for a few minutes and then they collapse back into their comfortable slouch. The sloucher uses the ligaments to support their body; the military-style posture requires the phasic muscles to support the body. Both fail to achieve the optimal state. The military-style posture leads to chronic tightness throughout the body (due to overuse of the phasic muscles) and sets the phasic muscles up for overuse injuries. Body alignment is not in an optimal position, limiting movement initiation. And the body still lacks true stability, as the tonic muscles are not being used to create stability. Certainly a military-style posture is not a good alternative to sloughing.

The String Method: Good, But Not Optimal PostureThere are some good books out there (specifically in the alternative health sections on the ancient Chinese practices of Qigong and Tai Chi) helping people achieve better posture by imagining that a string is suspending the top of their head in the air and constantly lifting them up (Figure 3). The body is then imagined to hang from this string. This approach is much better than either slouching or the military-style posture, and I recommend its use as a preliminary aide in achieving better posture. Instead of actively pulling the body out of a slouch (the traditional military-style posture), you are allowing a powerful image to do the work. This image often leads to far better alignment and increased action of the tonic muscles versus the phasic muscles. However, this approach has its limitations. The image of a string lifting the body up leads to a modified military-style posture. Both methods involve lifting the body against gravity (although the string method is certainly far superior to the military-style posture). This lift pulls our bodies out of alignment and creates unnecessary and injury-causing tension in the system.

Figure 3. The String Method: Better, but not optimal.The primary problem with the string method is the image of the string lifting us up. The upward pull of the string breaks our contact with the ground, but we are standing on the ground! We must engage the ground to find optimum posture. The ground is the key to optimal posture.

Optimum posture is achieved not when the body has a constant lift upon it, but when each region of the body is instead resting balanced and relaxed upon the region below it. Thus the head rests balanced and relaxed on the neck, the neck on the thorax, the thorax on the pelvis, all the way down until the feet rest balanced and relaxed on the ground (Figure 4).

Figure 4. Optimal PostureIn optimal posture, we are resting down, not lifting up, into the ground. Gravity pulls us down, and our balanced system allows the ground to push us back up. A more useful image than the string would be an energy force from the earth pushing stability into our feet. Imagine the force of the earth holding your body up. Each of the three other methods of posture we have discussed (slouching, military-style, and the string method) lead to, at best, sub-optimal posture. The following table may help to clarify the three methods we have discussed and show how they differ from optimal posture.

| | Slouching | Military | String | Optimal |

| Alignment | Very Poor | Poor | Fair | Best Possible |

| Achieved By | Relaxing on Ligaments | Phasic Pull | Lifting Up | Relaxing into Ground |

| Energy Required | Minimal | Maximal | Medium | Minimal |

| Injury Potential | Very High | Very High | Low | Lowest Possible |

| Strength Potential | Very Low | Low | High | Highest Possible |

The Vertical Compression TestPosture is not something easily learned through words — it must be felt. We can talk all day about optimum posture, but without experiencing it, you will gain no appreciation and learn nothing. So let's get to the practical side of things: the Vertical Compression Test (VCT).

The VCT was developed to test posture by challenging it through increasing the force of gravity through the postural system. Basically, the test involves pushing gently straight down through your partner's shoulder blades and rib cage to assess his or her response to the push.

Figure 5. The Vertical Compression TestDirections:

- The person to be tested (subject) stands in his or her regular posture and remains as relaxed as possible in this position.

- The tester stands behind and above the subject (use a stool so you can push straight down — this is important!).

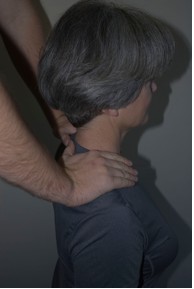

- The tester places a hand on the bulk of muscle on each side of the subject's shoulders (the upper trapezius muscle, basically the soft spot between the neck, collar bone, and shoulder) (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Place your hands on the upper trapezius muscle.

- The tester gently pushes straight down toward the floor. Bear in mind that you can hurt someone with this test. Push gently. Start with one pound of pressure and build from there. Increase your force slowly. And ask yourself (and ask your subject) if he or she buckles under the pressure? Do his knees start to bend? Do her hips start to flex? Does his spine start to bend backward? Notice I said, "start." You want to stop the test the second you notice the subject STARTS to buckle under the pressure. If the subject starts to buckle, the test is over; if she doesn't buckle, add more pressure. A person with optimal posture should be able to handle his or her own bodyweight without buckling while standing normally and remaining relaxed. If the person you are testing buckles before this point, record what percentage of his or her body weight you think you were delivering when the buckling occurred. Use this number as a measure for improvement over time. If you are carefully observing, 95% of the people you test will buckle way before his or her bodyweight is delivered, so watch carefully.

Notice that the directions never ask the subject to do anything. This is important. The VCT is a passive process for the subject. He or she should simply stand there and observe what happens to his or her body as the force of gravity is multiplied.

Go back to Figures 1-3 and perform a mental VCT on these postures (better yet, try to mimic the postures in the figures and have a partner perform a VCT on you). Can you see what gravity will do to the system? Can you see where injuries are likely to occur? Can you see why optimal posture is so important? Think about what happens to the person's body all day long because of poor posture.

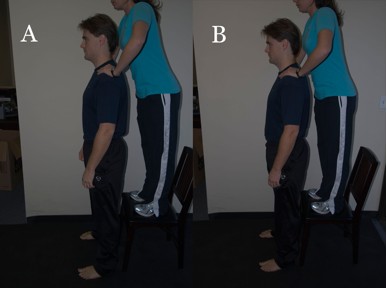

With the sloucher (Figure 7a), gravity is crunching the joints of her lower back all day causing wear and tear and eventually osteoarthritis. Her forward head position forces her neck muscles to constantly hold her heavy head up all day long creating tension and pain. Her rounded shoulders cause shortening of her chest muscles and an inability to reach above her head, limiting her strength and range of motion.

Hopefully it becomes painfully clear why the military-style posture is not a good alternative after performing a VCT on someone using it (Figure 7b). The extended lower back, just like with the sloucher, is still being crunched all day, but with the military posture, the joints of the neck are also being extended all day and the same degeneration will occur in there. The lifted chest changes the length-tension relationship of the abdominal muscles and significantly weakens them.

Figure 7. VCT on a Slouched Posture (a) and on Military-Style Posture (b).Although the dysfunction may be less pronounced, you will notice how the string method responds to a VCT in a number of poor ways. (Figure 8a). Most notably, you will notice a slightly elevated chest and slightly extended spine and neck. As already discussed, this posture is basically a mild version of the military-style posture and the same problems will exist.

Now notice how optimal posture responds to a VCT (Figure 8b). There is minimal tension in the system. You push down, and the ground pushes back up. The spine is aligned smoothly and doesn't buckle with the force of the VCT. The shoulder blades are back and resting down on the rib cage, thus the chest is not elevated or depressed, but simply relaxed in a neutral position. The abdominal muscles are relaxed with a natural tension built as they hold the abdominal contents in. The neck is neither forward nor extended, but balanced evenly over the rib cage. There is no obvious points of stress in the system.

Figure 8. VCT on the String Method (a) and on Optimal Posture (b).Remember that trying to understand these concepts by reading words and looking at pictures will get you nowhere. The pictures may give the impression that there is little difference between the postures, but performing a VCT makes the differences painfully clear. I strongly recommend you FEEL these concepts, not just read them.

Tight-Man Syndrome: False-Negative Vertical Compression TestMany strong individuals will attempt to overcome poor posture with tightness. They think that their strength will carry them through the day — and it does, but it causes many problems while it does so. By tightening their muscles they are able to maintain stability even with potentially horrible posture. However, they are relying on phasic strength to perform a tonic activity. Instead of slouching, these people will tighten their stomach muscles, tighten their glutes, tighten everything, and walk around like a stiff board. The phasic muscles, although strong, will become injured through the same mechanisms as repetitive movement injuries. Their phasic muscles will be chronically contracted, lack flexibility, and be painful to the touch. If you do a VCT on these individuals they will feel solid, and you can quickly overlook their problem. Their bodies are under chronic compression — all the muscles are binding them down, reducing their ability to move freely, compressing their joints (which will lead to early arthritis), and constricting their internal organs (decreased peristalsis and decreased ability to breathe). It is because of the Tight-Man Syndrome that the VCT must be performed when the subject is relaxed. Missing this key ingredient will lead to many false-negative tests, especially in the world of fitness (and even more so with strong Kettlebell lifters who don't want to show the slightest hint of weakness).

Optimal PostureOptimal posture is a state where the body is perfectly balanced over the ground, a state where each segment of the body is balanced on the segment below it so that minimal muscular work is needed to maintain position. The cranium rests on the first cervical vertebrae, the first cervical vertebrae rests on the second, and so on, so that the shoulder blades rest on the rib cage, the pelvis on the femurs, the femurs on the tibias, the tibia on the bones of the feet, and all in such a way that minimal muscular work is required to maintain the position. It is also the position where the rib cage and abdominal viscera have full freedom of movement: breathing and digestion are free and unencumbered. When our posture is correct, we can move freely in any direction with little effort. To move forward, we simply lean forward, to move backward, we simply lean backward, etc. Optimal posture is where we are designed to be and where our strength potential is maximized.

To achieve this state of ultimate balance, one must be very flexible, possess great soft tissue mobility, and have properly functioning tonic musculature (stability). Most of us don't possess these qualities to the extent necessary to achieve optimal posture. Specific treatment from a skilled manual physical therapist or a consistent program of home exercises specifically designed to enhance posture will be necessary for most people to come even close to achieving optimal posture.

The VCT acts as our guide in achieving optimal posture. When you can remain relaxed while your partner performs a full bodyweight VCT and you do not buckle, you have achieved optimal posture. Your partner will feel as though you are "springy." As if your body somehow absorbs the force of his or her pressure evenly, that the ground pushes back up through your body, and that when his or her pressure is slowly released, your body gently and evenly expands against the releasing pressure. The only way to find this position is to experiment, but there are some guiding principles you should work with.

Looking at your partner from the side, the center of the knee joints should rest slightly in front of the ankle joints, a gentle curve should exist in the low back and the opposite curve in the upper back, the shoulders will rest directly above the hips, and the ears directly above the shoulders. These guiding principles should serve to help you find problems in your partner's posture and give suggestions to correct those problems. I suggest two competing methods for correcting posture: 1) always begin the correction where the most significant dysfunction is, and 2) always begin the correction from the bottom up (start at the feet and work your way up to the head). Both of these methods are important, but they often conflict with one another. Only experience can tell you which to listen to in any given case. The important thing is to not try to correct your head position when your upper back is way off, and not to spend all your time on a minor shoulder alignment problem when your lower back is so arched it could crack with your next step off a curb.

Do not expect to achieve optimal posture right away. For now, settle on small improvements: an increase in your VCT (your partner reports that more force is needed before you buckle), you feel less strain when standing, you fell more ease in movement, etc. More than likely, you will not be able to physically achieve optimal posture because of mechanical restrictions limiting your ability to move certain joints and tissues of your body. If you want to improve quickly, seek out a skilled manual physical therapist. If you don't mind putting in some time and effort, slow and steady self-treatment can free many restrictions that limit your ability to achieve optimal posture. Look for future articles covering potential exercises that can be used to free the body for optimal posture. For now, basic flexibility and joint mobility drills like those taught in Pavel's books are highly recommended (Relax into Stretch, Super Joints, and Resilient are great for this purpose). Of prime importance are ankle, hip, and chest flexibility, so focus there.

The Kettlebell PostureApplying postural work to your kettlebell training will help you learn faster and will assist your development of strength, speed, and stamina through our kettlebell training. When optimal (or at least, better) posture is achieved, the tonic muscles do their job to stabilize the body, allowing the phasic muscles to focus on what they do best — lifting and moving the bell.

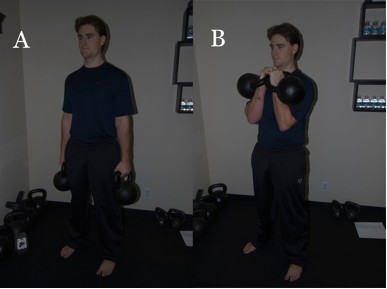

When some improvement has been made with your posture, reinforce your postural gains with kettlebell stands: farmer's stand and racked-position stand (Figure 9), eventually progressing to walking while holding kettlebells in these positions. Every second you stand and every step you take will be a VCT because the kettlebell will be adding to gravity and the force of the ground pushing back up against you will create the shock wave needed to test your system's response.

Figure 9. Farmer's Stand (a) and Racked-Position Stand (b).It is vitally important that you pay close attention to your body during these drills. Is there any segment of your spine that buckles with every step? Are you raising your shoulders to compensate for your lack of optimal shoulder blade posture? Do your knees hyperextend with each step? Where is the stress going? If the stress is going anywhere except straight down to the ground then something's wrong. Your system is not distributing the force optimally and injury will likely result. I shouldn't have to say that these drills should be done with light kettlebells. These are reinforcement drills, not exercises. Use them to reinforce your posture, not test its limits. They become exercises only once you have achieved optimal posture and you want to challenge that posture. [Note: These same drills are commonly performed with heavy weights. I am not arguing against this practice (in fact, I prescribe heavy kettlebell walks on a regular basis), but the trainee must maintain tightness throughout the entire drill if using heavy weights — like the Tight-Man Syndrome. When tension is lost, it becomes a VCT and can cause injury. Either do the drill with heavy weights and maximally tense your body, or do it without tension and use light weights to test and reinforce your posture. Don't mix and match. Be smart: understand why you're doing what you're doing.]

These simple kettlebell stands and walks will reinforce whatever gains you make in your posture through flexibility and joint mobility drills. I recommend having a partner perform a weekly VCT to see how you've improved. Over a few months of consistent practice, you should see a dramatic improvement in your posture and a dramatic improvement in overall strength and speed. You will also have a significantly lower chance of getting injured.

Posture, like breathing, is one of the key physical links to our overall health. Our emotional states are reflected through our posture. We can actually change the way we feel by changing our posture. And posture dictates much of what will happen to our bodies over time. Poor posture places abnormal stress on our bodies and delivers early arthritis and many chronic injuries; optimal posture strengthens our physiques and maintains our health. Posture's connection to breathing (optimal posture allows ample mobility of the thoracic cage and abdominal viscera) makes it of prime importance to our general physical health also. So work for better posture. Do it for your kettlebell performance; do it for your life.

About the AuthorDr. Jake Caldwell, DPT, CSCS, RKC is a physical therapist and owner of Primitive Therapy, a physical therapy and personal training clinic in Lake Forest, CA. Jake earned three bachelors degrees from the University of California at San Diego in Biology, Psychology, and History, and earned his Doctor of Physical Therapy from Chapman University in Orange, CA. He has since taken advanced manual therapy training through the Institute of Physical Art and, after training with kettlebells for years and using them to assist his patients, received his RKC in 2007. At Primitive Therapy, Jake combines the skills of manual physical therapy and hard-style Kettlebell training to develop physical health and fitness. For further information, call Primitive Therapy at (949) 310-4276 or email kettlebells@primitivetherapy.com.

Back