Infinite Isometrics Part One: Isometrics and The Active Mind

By The Dragon Door Research Group

Science has unlocked many laws which enable us to more fully understand the principles of productive resistance exercise—i.e., exercise which can effectively increase human strength, muscle mass, or both. Unfortunately, most discussions amongst the fitness public in the modern era (particularly online) revolve around nutrition and the use of Performance Enhancing Drugs. As regards training, some chatter is directed to ideas such as "the best rep range for hypertrophy" or "is it best to go to failure or stop short?" but beyond this it is assumed that most training science is, fundamentally, settled. Almost religiously so.

The dogma of this "settled" status quo can be summarized in three points:

- Barbells and dumbbells are necessary for building maximum strength and muscle;

- The best exercises for building strength and muscle involve a full range of motion;

- Muscles grow and get stronger by being torn down, then given adequate rest to rebuild better.

Right there—in those three core ideas—you have encapsulated almost all modern resistance training ideology, as it is understood by the majority of the fitness public. Speak to trainees—in the gym or online—and you’ll quickly discover that these sacred cows are hardly ever questioned. They are ingrained dogma.

Unfortunately, all of these ideas are incorrect.

Let’s examine the first statement. Most athletes and coaches seem to be brainwashed into believing that barbells and dumbbells are essential for maximum muscle and strength gain.

This idea will perhaps seem peculiar to the average physiologist. Why? Because muscle cells are simple, binary mechanisms. They either turn on, or they don’t. This is a well-established principle of motor recruitment known as the all-or-none law. Muscle cells have absolutely no idea what they are lifting—whether barbells or dumbbells, selectorized machines, your own bodyweight, a digital handle, or a bag of rocks. All they understand is resistance. Yep, barbells offer progressive resistance. So do machines (and bags of rocks, for that matter).

Barbells and dumbbells are not necessary.

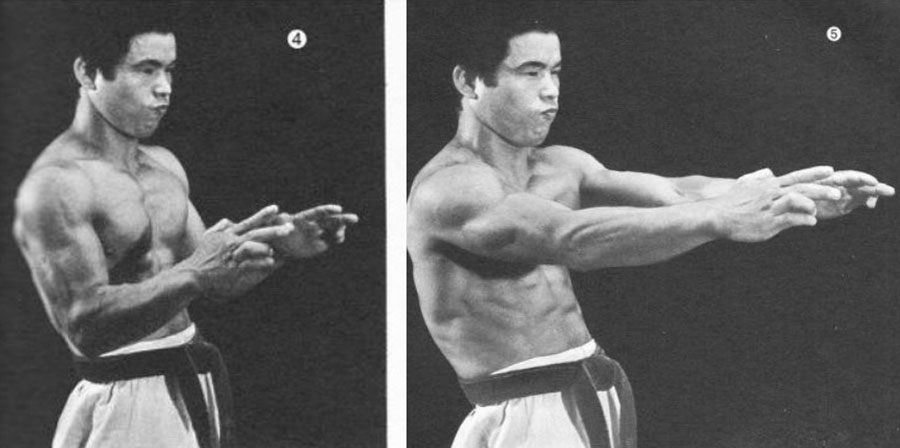

In classical martial arts, strength was developed by mastering the body’s internal

tension—external weights were seen as secondary. This is called ibuki in Japanese karate.

(From Oyama’s "Mastering Karate", 1966.)

If the all-or-none law is true—and it is—another consequence is that muscles have no idea if they are moving. Individual cells either contract or they don’t. Whether a limb or bone adjacent to a joint moves as a result entirely depends upon whether

enough individual motor units fire to overcome whatever load is keeping them static.

If you have grasped this fully, you will immediately see that the second idea listed above—that a full-range of motion is required—is completely meaningless.

Movement through space is really controlled by the brain. Muscles don’t know if they’re moving or not: therefore range of motion bears almost no relation to muscular training. Muscles only "understand"

intensity of contraction—in terms of a proportion of motor units being activated. Movement, or range or motion, is entirely incidental to that.

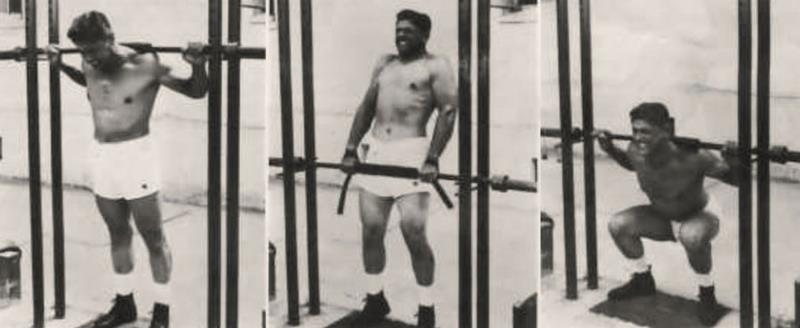

Champion weightlifter Louis Riecke works out in the isometric rack: using zero motion.

So, what about the idea that we "tear" our muscle cells down in training, to allow them to rebuild stronger? This (very old) concept is obviously based on the tissue healing model. Unfortunately, there has never been any serious evidence that this is how muscles work.

Recall that motor units are

binary—they don’t have an intensity switch, like a light dimmer. They can only fire completely or not at all (hence

all-or-none). Therefore we gain strength primarily

by teaching our body to turn on more motor units. This happens through repetition, due to a neurological phenomenon called Hebb’s rule. Muscle damage plays no role.

Just as muscle damage doesn’t build

strength, nor does it cause

growth. Muscle hypertrophy has been proven to optimally occur in the absence of muscle damage. Damage is only incidental to the process, not a cause. This should actually be obvious if you think about it for a moment: marathon runners cause their muscles massive damage while training or racing, and if damage really is the trigger to growth, they would be the world’s largest athletes, not the smallest.

(In case you were wondering—

metabolic stress plus

mechanical tension are the major drivers of muscular growth. Gym bros are actually getting close to the mark with the more recent "time under tension" mantra. Even a stopped clock is right twice a day.)

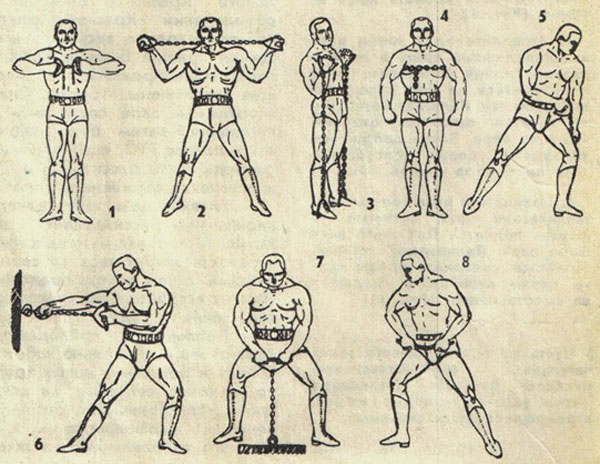

Old school isometric chain training causes virtually no muscle damage;

Old school isometric chain training causes virtually no muscle damage;

but made strongmen of the time powerful enough to break chains and bend iron bars.

So far, we have looked at the major principles of resistance training in light of just ONE well-established scientific principle—the

all-or-none law. Even a rudimentary understanding of that law has shown that the current sacred cows of resistance training—the necessity of barbells and dumbbells, full-range of motion, and tissue damage—actually make very little (or no) sense.

If the understanding of just one scientific law can illuminate training ideology this much, what would it mean if we understood more? If we completely grasped

ten such laws, for example? How much more enlightened could your thinking become? How much could such a knowledge amplify your training, how much wasted time and energy could it save you in your training career?

In this series of articles, we are going to build a complete encyclopedia of resistance training principles. These will not be "broscience" principles (leg extensions for cuts, squats for mass, etc.), but bona fide and established laws of physiology—well-known to any exercise scientist worth his or her salt, but not to those people who really need them the most—the average gym-goer or home-training athlete.

We will be examining a range of subjects essential to a solid understanding of resistance training—and

isometrics—including topics such as the all-or-none law, the force-velocity relationship, Davis’s law, Hebb’s law, Henneman’s size principle, etc. Crucially, each article will conclude with a "take home" section, giving you to apply the lessons of science to your own training—for maximum strength amplification, muscle gain and recovery speed. If you have been wanting to really get under the hood of exercise science, and take your training to the next level, this is the series for you.

The biggest challenge to

making isometrics work is having an open enough mind to try it. That’s why—when you come across athletes who fully embrace isometrics (think: Bruce Lee, Louie Simmons, Dan John, Pavel, etc.), these people are inevitably the athletes and coaches who have the most open—and

active—minds about training methods. Isometrics looks (and feels) so different from the established conventional methods that, if you are a "group thinker" it will be almost

impossible to accept the discipline from the get-go. But if you are one of those rare individuals with an open and active mind, we are hoping to invite you to explore a method of training that will change your life. This is not hyperbole.

Isometrics is not only the most efficient method to increase muscle and strength, it also builds speed, amplifies athleticism, heals bad joints, decreases pain, and improves blood pressure and cardiovascular health.

If you are unwilling to consider unconventional methods of training, we hope that these articles will change your mind. So what if the mainstream is married to the typical lift-it-up and put-it-down methods of training? The notion that something must be true because the majority accept it is in itself a logical fallacy—

argumentum ad populum (Latin for "appeal to the crowd").

Anyone with any knowledge of the history of science readily understands that there is nothing magical about "consensus", now or ever. To quote the great author Robert Heinlein:

does history record any case in which the majority was right?

Back